Andrew Hallam

11.09.2020

Investors: Don’t Stuff Logic in the Trunk of Your Car

_

You get behind the wheel of your car, put on your seatbelt and start the engine. You look for oncoming traffic before accelerating onto the street. In most cases, logic determines your decisions. It rides in the seat beside you. It suggests when to accelerate, brake or turn. When you’re distracted, logic sits in the back. This might not be safe. But you can still hear its voice when tuning out the noise.

This isn’t the case with investing. Logic rarely rides shotgun. It rarely rides in the back. More often, it’s stuffed in the trunk where you can’t hear its muffled voice.

I used to live on an island. To get to the mainland, I drove my car to the ferry. If, one day, I were foolish enough to drive at 130 miles per hour, instead of 50 miles per hour, it might have helped me catch a boat. But it would have been nuts to say, “I’m making great progress at 130 miles per hour, so this is a smart decision.” Even if I arrived safely at the ferry, my plan to drive like that would have bordered on insane.

Smart drivers consider downsides and worst-case scenarios.

That should be the case with investing, too. But far too often, we judge the intelligence of a decision based on the short-term result.

Imagine somebody saying, “Five years ago, I invested my entire life savings in five stocks: Apple, Amazon, Netflix, Google and Facebook.” The investor says, “That money soared, so I made a smart decision.” Herein lies the delusion. Even if it worked, that wouldn’t have made it smart. Instead, it would have been like surviving that 130 mile-per-hour race for the ferry.

Smart investors ask, “What’s the downside?” They know they can’t see the future. They know nobody else can, either. That’s why they diversify with a portfolio of low-cost stock and bond market index funds. They don’t speculate, chasing hot stocks, gold, Bitcoin or Beanie Babies.

Over the past 20 years, I’ve joined several investment forums ranging from the Motley Fool group in the late 90s to Facebook groups today. Far too often, I see logic stuffed in trunks.

In 2017 and 2018, forums filled with an insatiable thirst for Bitcoin. Participants said they were smart to buy Bitcoin because it increased in value. They sought stories to confirm its rosy future. In December 2017, the crypto-currency topped $20,000. This prompted me to write, Bitcoin Investors: Here’s Why Your Children Might Ignore You.

Not long after that story’s publication, hopes and dreams were dashed. Bitcoin currently trades at about $11,000.

At least once a decade, gold fevers rage. Such is the case, today, as seen on plenty of investment forums. Unfortunately, gold’s downside is huge. The price of gold drops more frequently than the stock market. And over the past 220 years, its long-term profits have been horrific. In fact, despite its recent run, gold is roughly the same price (after inflation) as it was in 1980 and 2011.

This might look like a couple of cherry-picked years. But in Claude Erb and Campbell Harvey’s 2013 study, “The Golden Dilemma,” the wage of a Roman centurion (in gold) equaled the equivalent buying power of a U.S. Army captain’s salary today. They also found that a loaf of bread, thousands of years ago, was about the same price today, when compared to the relative price of gold. I provided further detail in my column, Is Gold A Safe Lifeboat Now? Unfortunately, many people now say, “I recently poured money into gold and it went up in value.” They’re implying their decisions were smart, based on their outcome or somebody else’s story. But instead, investment decisions shouldn’t be judged on how they turn out. They should be judged on their range of probabilities instead.

That’s one of the things I like about financial advisors who work with Dimensional Funds. Before investors decide on their tolerance for risk, the advisors usually show a matrix of possibilities based on history or a Monte-Carlo simulation. In other words, they show worst-case scenarios, best-case scenarios, and the probabilities of each.

This isn’t an exact science. It is, however, smarter than forecasts, stories and wild speculation. To maximize the odds of long-term profits, don’t stuff logic in the trunk. Put a seat belt around it. Make it ride shotgun. As with driving a car, always consider the downside of decisions.

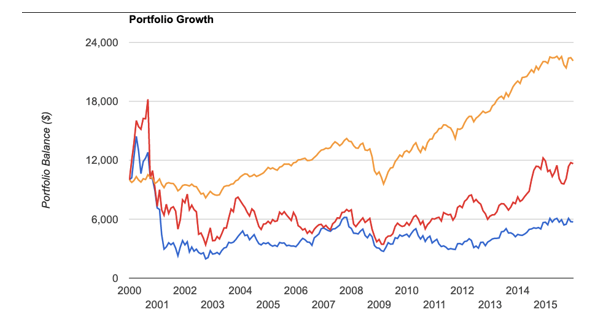

For example, consider a non-diversified portfolio of popular, high growth stocks. Many such stocks are coveted today. We can’t see the future. But we can ask, “What’s the historical downside?” In 2000, Intel and Cisco Systems were two of the most game-changing companies on the planet. Unlike many tech companies during the dotcom boom, these weren’t pipedream companies that didn’t earn corporate profits. They were (and still are) Behemoths that printed money. They were also debt-free. Their futures were brighter than retina-ripping lights. One of the world’s most respected investment guides, The ValueLine Investment Survey, predicted their stocks would keep rising. But after phenomenal share price growth in the 1990s, both stocks faltered. Over the 15-year period from 2000-2015, they lost to inflation. Over the 20-year period from 2000-2020, they underperformed a balanced index fund (60% stocks, 40% bonds) by roughly 100 percent and 200 percent respectively. That’s the painful downside of buying “can’t miss” stocks and not diversifying.

Balanced Index Fund Thrashes The Biggest “Can’t Miss” Stocks 2000-2015

Growth of $10,000 Invested

January 1980- July 31, 2020

Balanced index fund

Cisco Systems

Intel

Source: portfoliovisualizer.com

The intelligence of an investment decision shouldn’t be judged based on stories, hopes, forecasts…or an isolated result. Bitcoin, gold and popular stocks are long-shot dreams, much like playing in a casino. The long-term odds of knowing what and when to buy are very poor indeed. As I explained with these links, professional hedge fund managers, college endowment fund managers and tactical asset allocation managers speculate all the time. But they usually fall flat.

That doesn’t mean you can’t make money speculating. But much like driving at 130 miles per hour, the downside is huge. Instead of listening to your inner Kamikaze, put logic up front. Diversification reduces risk. Build a diversified portfolio of low-cost index funds. The intelligence of a plan should be judged on probable gains and losses. Always ask, “What’s the downside here?” And when doing so, use long-term history or a Monte Carlo simulator (especially for retirees) instead of a fortune-teller’s story.

Andrew Hallam is a Digital Nomad. He’s the author of the bestseller, Millionaire Teacher and Millionaire Expat: How To Build Wealth Living Overseas

Swissquote Bank Europe S.A. accepts no responsibility for the content of this report and makes no warranty as to its accuracy of completeness. This report is not intended to be financial advice, or a recommendation for any investment or investment strategy. The information is prepared for general information only, and as such, the specific needs, investment objectives or financial situation of any particular user have not been taken into consideration. Opinions expressed are those of the author, not Swissquote Bank Europe and Swissquote Bank Europe accepts no liability for any loss caused by the use of this information. This report contains information produced by a third party that has been remunerated by Swissquote Bank Europe.

Please note the value of investments can go down as well as up, and you may not get back all the money that you invest. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.