Dossier

Music, a beaming industry

Now that concerts are back on and streaming continues to attract more users, 2022 is shaping up to be a record year for the music industry. That’s a tremendous turnaround for a sector that was languishing just 10 years ago.

By Bertrand Beauté

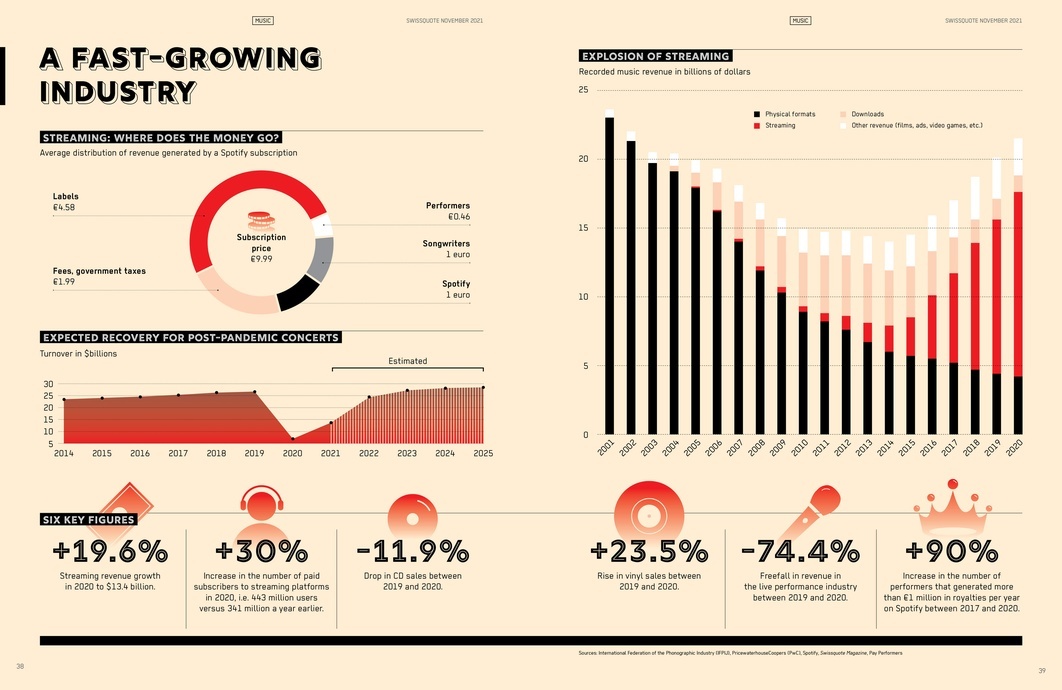

Before you start reading this article, crank up the volume on your amp and listen carefully to the first notes of "Money", the timeless 1973 classic by Pink Floyd. The rhythmically clinking coins make for the perfect introduction to this special report. Because yes, music is making money once again. Despite the pandemic, in 2020 the recorded music industry generated sales of $21.6 billion, up 7.4% from one year earlier, marking the sixth consecutive year of growth. And this is just the beginning. "We’re just now in the early stages of the music industry’s renaissance," says Alexandre Phily, an analyst at Union Bancaire Privée (UBP). "The sector still has huge growth potential." Richard Speetjens, portfolio manager of Global Consumer Trends strategy at Robeco, agrees. He predicts that "music revenue will continue to grow at an annual rate of 7% to 10%".

And investors are loving it. On 21 September, the world’s largest recorded music company, Universal Music Group (UMG), rocked a show-stopping IPO on the Amsterdam stock exchange. The company’s stock is currently trading at around €24, more than 30% above its IPO price. A year and a half earlier, in June 2020, Warner Music’s IPO was already a hit. The world’s third biggest music company, behind Universal and Sony, was valued at $15 billion when it came on the stock exchange stage. Fifteen months later, its capitalisation has soared to close to $23 billion.

Not bad for an industry that was practically on its death bed 10 short years ago. Now let’s back up a bit. In the late 1990s, major record labels were singing, flamboyant and carefree. But like the fabled, ill-fated cicada, they paid dearly for their short-sightedness in coping with the devastating onslaught of illegal downloads. After culminating at $28.6 billion in 1999, the global recorded music market collapsed and fell more than 50% in 15 years to $14 billion in 2014, according to figures from the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI). Since then, the sector has slowly but surely regained strength with the emergence of a new technology: streaming, i.e. listening to music online, has provided new ways of monetising music after years of piracy.

"Paid streaming has brought people an all-new type of service," says Alexandre Phily of UBP. "One click gives consumers access to a music library, with no storage limit or download time. And that has decimated piracy. Users would rather pay a subscription fee to listen to music than download for free." Virtually non-existent in 2010, streaming generated more than $13 billion in revenue in 2020, i.e. 62% of the recorded music industry’s total revenue. This breakneck growth has not been derailed by the pandemic, quite the opposite.

"WE ARE JUST NOW IN THE EARLY STAGES OF THE MUSIC INDUSTRY'S renaissance"

Alexandre Phily, analyst at Union Bancaire Privée

A £10 monthly subscription is something pretty much everyone can make, says Merck Mercuriadis, CEO of Hipgnosis Songs Fund, in an interview with The Guardian. "And, as has been proven during the pandemic, those subscriptions have gone up as people have gone looking for comfort." In Q1 2021, 487 million subscribers worldwide paid for streaming services, up from 341 million at the end of 2019. And Hipgnosis predicts in its annual report that the figure will exceed 2 billion by 2030. "The number of users will continue to rise," Alexandre Phily says. "Less than 15% of smartphone owners across the globe currently have a paid subscription to a music streaming platform. Growth potential is still huge."

LABELS WIN BIG

The many music streaming platforms (Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon Music, Tencent, YouTube, Tidal, Deezer, Qobuz, etc.) pay a considerable chunk of their revenue – about two-thirds – to the big three labels, Universal, Warner and Sony. The trio controls 70% of the music market and owns most of the song catalogues.

For example, world leader Spotify paid more than €5 billion to rights holders in 2020 out of its total revenue of €7.9 billion. That came out to a net loss in 2020 of €581 million for the Swedish star. Meanwhile, Universal Music, which generates revenue comparable to that of Spotify (€7.432 billion in 2020), made a comfortable profit of €1.2 billion.

"It’s a very good time for music labels," says Uwe Neumann, an equity analyst at Credit Suisse. And streaming is not the only thing driving the music industry. "Although it’s not their main purpose, social media such as TikTok, Snapchat and Instagram are using a growing amount of music" says Phily from UBP. "This delivers another way to make money for the music industry." And now they’re all partnering up. In January and February 2021, Warner and Universal signed agreements with TikTok to reap "equitable" compensation from the platform which, until then, paid little or nothing for the music it plays. Then, last June, Universal signed a licensing deal with Snap, the parent company of the photo and video sharing app Snapchat. Other companies, such as smart bike maker Peloton and video game publisher Roblox, are also paying more royalties. For the first time, we’re at a "point when almost all consumption is now paid for", Hipgnosis boss Merck Mercuriadis said in the investment company’s 2021 annual report.

HITS NEVER DIE

Music labels aren’t the only ones in tune with the times. The music industry’s restored financial health has attracted ferociously hungry new players – publicly traded investment funds, enticed by royalties and predictable returns. The best known is Hipgnosis Songs Fund Limited, which has been listed on the London Stock Exchange since 2018. In May 2021, the company paid $140 million to acquire the entire Red Hot Chili Peppers catalogue. These rights will further pad an already star-studded roster featuring Mariah Carey, Shakira and Neil Young. That means that now, when a commercial, TV station, or streaming platform such as Spotify plays "Under the Bridge", the biggest hit by the US rock group Red Hot Chili Peppers, the revenues generated (royalties in biz-talk) will no longer funnel into the pockets of the band members or their label, but go straight to Hipgnosis.

The British fund is not alone in this niche. Other players include the private equity firm KKR, better known for its portfolio investments, or the dedicated American fund Round Hill Music. In the face of these hungry financiers, traditional labels are not sitting around idle. In December 2020, Universal bought 600 Bob Dylan songs for an estimated $300 million. Then in April 2021, Sony Music acquired Paul Simon’s catalogue, which includes the hits "Mrs. Robinson" and "Sound of Silence" by the famed duo Simon and Garfunkel, for an unconfirmed sum believed to exceed $200 million.

Streaming has provided new ways of monetising music after years of piracy

Naturally, these stratospheric prices are prompting more and more rock’n’roll veterans to sell their recording rights. But is this reasonable for the buyers? "Songs are more reliable assets than oil or gold. A classic song is a source of predictable income in an unpredictable world," Merck Mercuriadis, head of the Hipgnosis fund, told The Guardian. Here again, the streaming revolution has reshuffled everything. In the past, consumers would buy a record, and rights holders would only receive their royalties at the time of purchase. As sales dwindled, so did revenue. But with streaming, royalties are paid with every listen. It doesn’t matter how old the song is.

"Streaming shows that consumers like to listen to old songs," says Richard Speetjens, portfolio manager of Global Consumer Trends strategy at Robeco. "Old catalogues actually retain a lot of value." Especially these days, when internet buzz can revive a forgotten track and send it back to the top of the charts. That’s what recently happened with "Dreams", the iconic hit by the British-American band Fleetwood Mac. Released in 1977 on the group’s Rumours album, the song had a successful career, reaching number one on the Billboard Hot 100 in June of that year, before slowly fading from the charts.

Forty-three years later, in September 2020, an American dad filmed himself skateboarding down a highway while listening to "Dreams". Once posted on TikTok, his video went viral.

"A classic song is a source of predictable income in an unpredictable world"

Merck Mercuriadis, CEO of the Hipgnosis fund

More than 100,000 people viewed it in less than an hour. Unexpectedly, all the buzz propelled the song back into the Billboard Hot 100, where it reached No. 21 in October 2020. That convinced German music management group BMG Rights Management to buy the rights from Mick Fleetwood, co-founder of Fleetwood Mac, in January 2021. To justify its purchase, BMG calculated that, in the space of about eight weeks, "Dreams" generated 2.8 billion views on TikTok and was streamed 182 million times.

LOSERS OF THE PANDEMIC

The music sector may be powering ahead, but it is also leaving large swathes of industry players by the wayside. Concert, festival and tour organisers, as well as venue owners, were hit hard by the pandemic. PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) predicts that live music revenue, which fell by 74.4% in 2020 compared to 2019, will not return to pre-pandemic levels until 2023. But that doesn’t worry Richard Speetjens. "Demand is currently high for concerts," the Robeco manager says. "Musicians who haven’t been able to perform for such a long time want dates, and audiences are eager to get out and see live performances after months of lockdown. The concert industry will make a strong comeback in 2022 if the pandemic is contained."

This is good news for Live Nation Entertainment, the world’s leading concert company. Prior to the pandemic, it was running 40,000 shows and over 100 festivals a year, selling 500 million tickets. "The popularity of live performance did not abate during the pandemic. Many festivals are already sold out for next summer," says Alexandre Phily, the UBP analyst. The recovery of live performances will be fuelled even further as labels push their artists to tour, because the experience of live music creates fans, which leads to more listening on streaming platforms – therefore more income for labels." Abba, who in 2021 released their first album in 40 years, will agree. The interstellar Swedish band will be touring again in 2022, to the tune of their iconic hit "Money, Money, Money". The song came out in 1976, but has lost none of its relevance in the music industry.

WHO DOES WHAT IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY?

SINGER-SONGWRITERS

Artists are the lifeblood of the music industry. Songwriters, also called composers, write the music and lyrics, while the performers perform the written work. They may be one and the same person. It is impossible to estimate the total number of artists in the world. Spotify alone has more than 1.2 million artists with more than 1,000 listeners. Of those artists, 870 generated more than $1 million in royalties on Spotify in 2020 and 7,800 more than $100,000.

LABELS

Previously known as record companies or record labels, labels or “majors” are responsible for managing artists’ careers. Major labels held 32.1% of the market in 2020. Universal Music Group is the world leader, followed by Sony Music Entertainment (20.6%) and Warner Music Group (15.9%), according to Statista. A multitude of independent labels, such as Believe, split the remaining 30%.

PLATFORMS

Several hundred music streaming platforms, including Deezer, Tidal, SoundCloud and Pandora, are in operation around the world, but only a handful cover the bulk of subscribers. Midia Research estimates that the Swedish platform Spotify held a 32% share of the market in the first quarter of 2021, with 165 million paid subscribers, followed by Apple Music (16%), Amazon Music (13%), China's Tencent (13%) and Google (8%).

CONCERT ORGANISERS

Music tours are becoming more global and are increasingly organised by entertainment giants. The US company LiveNation is number one in the industry and owns the ticketing company Ticketmaster. Before the pandemic, it organised over 40,000 shows and more than 100 festivals each year. AEG, an American firm, holds second place and organises around 20 festivals a year.

FANS

No way could anyone reliably count the number of people who listen to music worldwide. IFPI figures show that only 443 million listeners had a paid streaming subscription at the end of 2020, while YouTube’s free service counts more than 2 billion users per month. In 2018, the average time spent listening to music was 18 hours per week, according to a study conducted in 19 countries.

THE NFT REVOLUTION

After exploding into the art world, non-fungible token (NFT) technology has made a grand entrance into the world of music in 2021. So what are NFTs? NFTs are digital tokens registered on a blockchain and can therefore not be forged. When attached to a work of art, they provide a sort of certificate of authenticity and can make unique what is not. For example, a digital image that can be duplicated infinitely is worthless. But if combined with an NFT token, it becomes a unique work. For example, in March 2021 a digital collage by the American artist Beeple was auctioned at Christie’s for $69 million. The buyer did not actually buy the work itself but the associated NFT.

These days, songs too are digital works, like some contemporary art. And the music industry could not remain an outsider. In March 2021, electronic music star 3LAU made $11.7 million by selling 33 NFTs at various prices. The most expensive included a custom song, access to new music on his website, custom artwork and new versions of the 11 original songs on his Ultraviolet album. Other artists such as Lil Pump, Grimes, Kings of Leon and The Weeknd have also sold NFT tracks. Consulting firm PwC says that NFTs are a significant innovation that enables artists to address their customers directly.