Ukraine

A brutal come-down expected for Europe

The war in Ukraine will have lasting effects on the global economy – how extensive those effects will be is currently unknown. While markets have returned to their pre-crisis levels, the shadow of stagflation weighs heavily on Europe.

By Bertrand Beauté

The war has turned the markets both hot and cold. "Since the start of the conflict, markets have forgotten the fundamentals a bit," says Mabrouk Chetouane, head of Global Market Strategy at Natixis Investment Managers. "They react to current events, following good and bad news, rather than tangible economic outlooks."

On 8 March, when peace talks were announced between Russia and Ukraine, the STOXX Europe 600 increased nearly 5% in one day. A few days earlier on 3 March, that same index, which is made up of the 600 largest European capitalisations, was down by 3.5%. Why? After a conversation with Russian president Vladimir Putin, French president Emmanuel Macron said the following: "The worst is yet to come," feeding the flame of chaos that has been disrupting the markets since the start of the invasion on 24 February.

"We’re going to see even higher levels of inflation"

Alan Mudie, chief investment officer at Woodman Asset Management

As a sign of this anxiety, the European volatility index VSTOXX – dubbed the fear index – reached nearly 60 points on 7 March, by far its highest level since March 2020, and then fell below 30 points by late March – its pre-crisis level. "Uncertainty about the war led to a certain nervousness from investors at the start of the conflict. But the situation is beginning to normalise," said Chetouane. “Markets adjust to everything. They adjusted to Brexit, to the China-US trade war, to COVID, to the annexation of Crimea... They will adjust to this crisis as well."

Indeed, as of the end of March, most European indices had already recovered their losses since 24 February – the day Russia invaded Ukraine. "Investors, who initially feared a breakdown in the Russian gas supply, escalating conflict in Europe, or even the outbreak of a Third World War, were somewhat reassured," says Hubert Lemoine, chief investment officer at Schelcher Prince Gestion. "They accepted the idea of a long conflict that remains limited to Ukraine, with a diplomatic agreement in the more or less long term."

But this market optimism seems to be at odds with the economic reality, particularly in Europe, which is on the front lines of this conflict due to its dependence on Russia for energy. "Before the war, inflation was already a threat. The invasion of Ukraine made the situation worse," said Chetouane. "According to our projections, inflation is expected to reach 5% in 2022 in the Eurozone and 2.9% in 2023. These are unprecedented levels." According to Eurostat, the annual inflation rate in the Eurozone was 7.5% in March, after a 5.9% increase in February. This is the highest level since the indicator was first produced in 1997.

This is due to the fact that the price of raw materials, energy and foodstuffs has increased since the start of the conflict. "We’re going to see even higher levels of inflation," warned Alan Mudie, Chief Investment Officer at Woodman Asset Management. "We need to keep in mind that this geopolitical crisis is here to stay. Europe wants to massively reduce its imports of Russian energy, but that will take time: 40% of natural gas consumed in the European Union comes from Russia, so a quick pivot is not possible! Energy prices could be high for a long time."

Mabrouk Chetouane agrees, saying "the height of inflation is still to come and should arrive in Q3." According to economists at Goldman Sachs, inflation will reach a maximum of 7.7% in July in the Eurozone.

Faced with increased consumption prices, households may slow their spending and companies could limit their investments. This would all lead to limited economic growth. In this context, the IMF has revised its 2022 growth outlooks for the eurozone to 2.8% from 3.9% in its January forecast. But Bank of America already predicted that European GDP growth would be no more than 2.4%. In relation to Switzerland, the economic institute KOF expects a 2.9% increase in GDP in 2022.

Adapting supply chains is a process that everyone must undergo

These estimates could be revised downwards even further over the course of the year. "Economists don’t want to announce outlooks that are too dire, too soon, so as to not scare off investors," said Lemoine. "In reality, the risk of stagflation in Europe – a period where high inflation coexists with stagnant economic growth – as we saw with the first oil crises in 1973 and 1979, is high. And if we’re not yet in a recession, we’re not far off. There are concerns that the economy could come to a screeching halt."

Christine Lagarde also said something along those lines: "The longer the war lasts, the higher the economic costs will be and the greater the likelihood we end up in more adverse scenarios," said the ECB President on 30 March. The risk is even higher given that inflation isn’t the only issue brought on by the war.

To receive their supply of raw materials, manufacturers must learn to bypass Russia. This is especially challenging given that Moscow is a significant supplier of minerals for Europe. For example, of the titanium used in their aircraft, Airbus and Boeing import 50% and 30% respectively from Russia. After breaking their contract with Russian giant VSMPO-Avisma, the global leader in titanium production, the two aviation companies need to find other suppliers. In another industry, Geneva-based firm Richemont, which owns the jewellery house Cartier, among others, has stopped using Russia for its diamond supply. Again, it must find an alternative, considering that the Russian mining company Alrosa holds 28% of global market share. Adapting supply chains is a process that "everyone must undergo," said Cyrille Vigneron, president and CEO of Cartier, at a watchmaking conference in late March. "That comes at a price that we don’t know yet."

Other Western companies had to flee the Russian market post haste, mostly due to pressure from consumers, even though they generated a substantial portion of their revenue in the country, including automotive manufacturer Renault. Russia made up 18% of Renault’s sales and 12% of its operating margin. Of course, this is an extreme case. Most European manufacturers are not very exposed to Russian and Ukrainian markets, which only represent at most a few percentage points of their revenue.

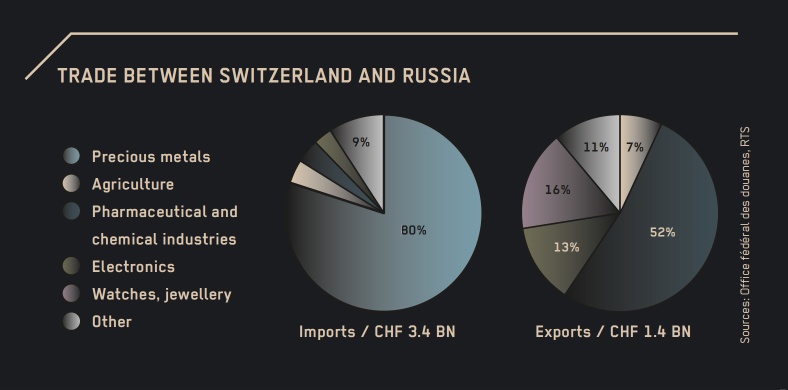

Swiss exports to Moscow, for example, were only worth 3.4 billion Swiss francs in 2021, or less than 1% of the total. "But the Swiss economy is a global economy, strongly linked to the rest of the world," said Eleanor Taylor Jolidon, co-head of Swiss and global assets at Union Bancaire Privée (UBP). "Sluggish global growth will have negative consequences for Swiss companies." This is because, apart from its direct consequences, all economic players will feel the side effects of the war, including inflation, as well as supply-chain disruptions. For example, Ukraine produces 70% of the world’s neon, an essential gas used to manufacture semi-conductors. This could lead to shortages. In a note published on 22 March, Allianz Research believes that "the indirect impacts of the war will be global, massive and immediate. The entire global economy will suffer from rising energy and raw materials prices, as well as additional supply chain problems."

According to a study published on 16 March by Swiss corporate union Economiesuisse, nearly one-third of all Swiss companies believe that the war has already caused supply chain issues and 50% believe that the war will have an impact on revenue. Some of the materials that are hard to come by include aluminium and wood, as well as production equipment, machines and semi-conductors. Most companies that we profiled in this issue confirmed that they are currently unable to put a cost on the financial impact of the war. "When public companies publish their Q1 and especially Q2 results, investors will find out which companies have been most affected by the crisis," Hubert Lemoine notes.