Andrew Hallam

03.02.2020

What Investors Need To Know About These Growth Indicators

_

Abinash Duper scrambles out of bed and joins his father at the breakfast table. "This is going to be a great year," Mr. Duper tells his son. "Our company is doing well." He straightens his tie and adds, "Son, our business isn’t the only one on the rise. Bangladesh’s entire butter industry is hotter than your grandmother’s curry."

Abinash rubs his eyes and asks, "Are we going to be rich, father?"

Mr. Duper smiles and says, "I think we will be…because I’ve just invested a bundle in a U.S. stock market ETF. U.S. stocks go crazy when Bangladesh produces a lot of butter."

OK, I can hear what you’re thinking. Only a fool would think U.S. stocks jump with butter in Bangladesh. And I would agree. But millions of investors fall for indicators that seem to make more sense…yet they break dreams and hearts.

Such broken crystal balls include economic growth and unemployment rates. Consider the periods from 1965-1982 and from 1982-2000. The first period represented one of the U.S. market’s most anemic periods for stocks. The Dow Jones Industrials was at the same level in 1965 as it was 17 years later, in 1982.

According to the DQYDJ (Don’t Quit Your Day Job) calculator, an investment in the S&P 500 index, with all dividends reinvested, barely beat inflation over these 17 years. Yet America’s economic growth, as measured by GDP, posted healthy numbers. It averaged 3.47 percent per year. That’s far higher than the country’s GDP growth over the past ten years (U.S. GDP averaged 1.83 percent from 2009-2019)

It’s also slightly higher than America’s economic growth during history’s strongest and longest bull market: 1982-2000. GDP growth averaged 3.45 percent. But over these 18 years, the S&P 500 averaged a whopping 18.50 percent. That beat inflation by about 14.7 percent per year.

U.S. Economic Growth and Stock Market Growth Aren’t Strongly Correlated

| Average Annual GDP Growth | Average Annual Stock Market Growth Before Inflation | Average Annual Stock Market Growth After Inflation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1965-1982 | 3.47% | +7.0% | +0.5% |

| 1982-2000 | 3.44% | +18.50% | +14.73% |

| 2009-2019 | 1.83% | +15.18% | +13.14% |

Source: DQYDJ, measuring the S&P 500, including reinvested dividends

So when an economic pundit predicts weak or strong stock market gains, sit back and smile. Even if they could predict economic growth (which most of them can’t) GDP changes don’t forecast how stocks will perform. Nor do unemployment figures.

Imagine rubbing a magic lamp and releasing a genie. She says, “Six months from now, plenty of Americans will be out of work. Unemployment will peak.” You believe what she says, so you sell your U.S. stocks. Unfortunately, spikes in unemployment don’t lead to dropping stocks. In his book, Markets Never Forget (But People Do), Ken Fisher lists 14 dates that were each six months prior to an unemployment peak. On average, U.S. stocks gained 31.2 percent one year later.

High Unemployment and S&P 500 Returns

| Six Months Before Unemployment Peaks | S&P 500 Returns In The Following 12 Months |

|---|---|

| November 30, 1932 | +57.7% |

| December 31, 1937 | +33.2% |

| July 30, 1946 | -3.4% |

| April 30, 1949 | +31.3% |

| March 31, 1954 | +42.3% |

| January 31, 1958 | +37.9% |

| November 30, 1960 | +32.3% |

| February 26, 1971 | +13.6% |

| November 29, 1974 | +36.2% |

| January 31, 1980 | +19.5% |

| June 30, 1982 | +61.2% |

| December 31, 1991 | +7.6% |

| December 31, 2002 | +28.7% |

| April 30, 2009 | +38.8% |

| Average | +31.2% |

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics; Global Financial Data Inc., S&P 500 total returns

If you’ve decided to wait for rising unemployment before investing in the market, you might have missed the point. This is just as likely to repeat itself as not. Economic indicators have little (maybe zero) correlation to how stocks will perform. When it comes to the market, randomness rules instead.

Some people, unfortunately, believe recessions are bad for stocks and that economic growth is good. But as I’ve written here, recessions are often great for stocks. And economic growth is a very poor indicator of stock market growth.

Yale University’s endowment fund manager, David Swensen, explained this in his 2009 book, Pioneering Portfolio Management. William Bernstein said the same thing in his book, The Investors Manifesto, which he first published in October 2009. Bernstein listed the fastest growing economies over the previous ten years. Then he compared their stock market returns to slower growing economies over the same time period. The slower growing economies earned higher stock market returns than the faster growing economies.

Consider the International Monetary Fund’s assessment of the fastest growing economies over the past five years. Not every country has a viable stock exchange. But China and India do. China’s GDP averaged 6.66 percent over the past five years. India’s growth was even higher. Their country’s economy grew by 6.86 percent per year. But these stock markets disappointed investors.

According to iShares, their stock markets grew by a compound annual rate of 4.47 percent and 6.8 percent respectively, over the five-year periods ending December 31, 2019. In contrast, the global stock market index averaged 8.74 percent and U.S. stocks averaged 11.65 percent.

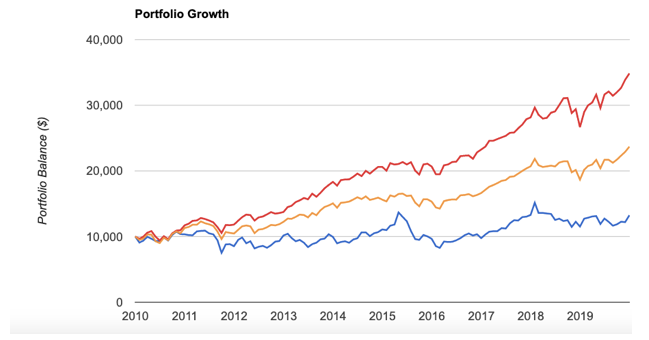

China’s GDP increased by a whopping 7.7 percent annually over the 10-year period ending 2019. Few countries matched that rate. But despite such rapid economic growth, the Chinese stock market was among the world’s worst performers. The iShares China Large Cap ETF (FXI) averaged a 10-year compound annual return of just 2.71 percent. Below, you can see how Chinese stocks performed compared to the U.S. and Global stock market indexes.

Fast Growing Economies Can Produce Weak Stock Returns

2010-2019

U.S. Stocks

Global Stocks

Chinese Stocks

Source: portfoliovisualizer.com

I’m not saying people should only invest in slow growing economies. Nor should they only invest during recessions or when unemployment peaks. Stock market returns are more random than we think. That’s why smart investors ignore economic news. They ignore forecasts. They build diversified portfolios of low-cost ETFs.

As for butter production in Bangladesh, it really does have a higher correlation to U.S. stock market growth than anything mentioned above. But correlation and causation are two different things. If you don’t know the difference, you might get egg and butter on your face.

Andrew Hallam is a Digital Nomad. He’s the author of the bestseller, Millionaire Teacher and Millionaire Expat: How To Build Wealth Living Overseas

Swissquote Bank Europe S.A. accepts no responsibility for the content of this report and makes no warranty as to its accuracy of completeness. This report is not intended to be financial advice, or a recommendation for any investment or investment strategy. The information is prepared for general information only, and as such, the specific needs, investment objectives or financial situation of any particular user have not been taken into consideration. Opinions expressed are those of the author, not Swissquote Bank Europe and Swissquote Bank Europe accepts no liability for any loss caused by the use of this information. This report contains information produced by a third party that has been remunerated by Swissquote Bank Europe.

Please note the value of investments can go down as well as up, and you may not get back all the money that you invest. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.