Andrew Hallam

23.04.2020

Financial Experts Trying To Time The Market Now

_

Who was the best basketball player of all time? If you hollered that question from an American sports bar, people would scream different names from every corner. The same thing might happen if you asked about history’s greatest tennis player, boxer, football player or hockey player.

But try asking this on Wall Street: Who is history’s greatest investor? You’ll likely hear one name: Warren Buffett. He’s among the four richest people in the world, despite the fact that, each year, he donates more money to charity than Donald Trump’s is worth.

Buffett has been Berkshire Hathaway’s chairman since 1965. When he first purchased shares, it was an ailing textile company. He soon turned it into an insurance firm. He used the company’s profits and insurance float to buy common stocks and dozens of private businesses. If someone had invested $100 in Berkshire Hathaway stock back in 1965, it would have swelled to more than $2 million by March 30, 2020.

You might wonder, then, how Warren Buffett is stickhandling through the most recent market drop. Did he sell everything before the market crashed? Or did he start to sell a little as the market started to plunge?

He didn’t do either in 1973/1974, when stocks fell about 50 percent. He didn’t sell in 1987, during the single-day 20 percent decline. He didn’t sell from 2000-2003, when stocks declined about 47 percent from peak to trough. Nor did he sell when stocks fell a similar amount from 2007 to March 2009.

How, then, was he able to turn $100 of Berkshire Hathaway stock into more than $2 million by March 30, 2020? One tip. He didn’t sell his investments.

In Berkshire Hathaway’s 2020 annual report he wrote, “Occasionally, there will be major drops in the market, perhaps of 50% magnitude or even greater. But…equities [stocks are] the much better long-term choice for the individual who does not use borrowed money and who can control his or her emotions. Others? Beware!”

Those last two words are the most important. “Others? Beware!” Buffett warns investors to control their emotions. He says neither he, nor anyone else, has a working crystal ball. That’s why he says:

“I have never sold any [Berkshire Hathaway] shares and have no plans to do so. My only disposal of Berkshire shares, aside from charitable donations and minor personal gifts, took place in 1980, when I, along with other Berkshire stockholders who elected to participate, exchanged some of our Berkshire shares for the shares of an Illinois bank that Berkshire had purchased in 1969 and that, in 1980, needed to be offloaded because of changes in the bank holding company law.”

Human instinct says it must be smart to jump out of stocks before they fall, and then jump back in when you (or some expert) says stocks are at their bottom.

Buffett doesn’t believe in that. He says, “We [he and co-chairman Charlie Munger] have long felt that stock market forecasters exist to make fortune-tellers look good.”

Those who don’t study Berkshire Hathaway’s annual reports or Lawrence Cunningham’s book, The Essays of Warren Buffett, might mistaken Berkshire Hathaway’s cash reserves for Buffett’s market-timing war chest: money he deploys solely for when stocks fall. According to Berkshire Hathaway’s 2019 annual report, the company had $129 billion in cash at the end of the calendar year. It represents 15 percent of Berkshire Hathaway’s assets (most balanced index fund investors have a greater percentage in bonds than Buffett keeps in cash). And although he pulls from this cash when he buys a new business, it’s earmarked for more.

Berkshire Hathaway covers all kinds of insurance needs… everything from automotive insurance to natural disaster insurance and, yes, even business closure insurance. Buffett uses this cash (known as an insurance float) to pay insurance claims.

Buffett doesn’t believe anyone, with any degree of consistency, can time the stock market. That’s why he doesn’t bother.

But plenty of others try. Hedge fund managers are among them. They lead their clients to believe they can make money when stocks fall. If they believe a drop is coming, they can “short the market”. This means they place bets that stocks will crash, and if they do fall hard, they collect on those bets. Some hedge fund managers keep money in cash if they think stocks will fall. By doing so, they hope to use that cash to buy stocks when they’re cheap.

But stocks can move very quickly. In just three days, from March 23rd to March 26th 2020, U.S. stocks gained 19 percent. Nobody saw that coming. When a hedge fund manager keeps money in cash, waiting for a further drop, or when they short the market, they usually end up with mud on their face. When stocks recover, professional traders rarely react fast enough to jump back into stocks. That’s because, like a great football dribbler, the market fools them with feints. Stocks will jump, then fall back. They will jump again, then fall back. Each jump looks like a false recovery. It’s one of the reasons most hedge fund managers get caught with their pants down when stocks eventually soar and keep going.

If you sold some of your investments because you think stocks will fall, you are thinking like a hedge fund manager. If you have suspended your regular investment contributions while you wait for the markets to stabilise, then you are thinking like a hedge fund manager. If you have money to invest but you want to wait for stocks to fall even further, you are thinking like a hedge fund manager.

You might be wondering, “What’s wrong with that?” Well…a lot. Nobody knows when stocks will hit their lowest point. Nobody knows how many times the markets will tempt us to speculate. We just know one thing. Those who speculate full time with other people’s money (like hedge fund managers) are like emperors with no clothes.

Consider 2008. Stocks fell hard. And nobody knew when they would hit rock bottom. Some hedge fund managers shorted the market on its way down. But like a trickster, the market used several upward feints to tempt these traders to jump in and out of stocks. As a result, when the real surge happened, they were too gun-shy to react.

HRI’s hedge fund research shows this to be true. In 2009, U.S. stocks increased by 26.46 percent. They increased a further 15.06 percent in 2010. Global stocks increased by 30.4 percent in 2009 and 8.62 percent in 2010. Unfortunately, global hedge funds didn’t fare as well. They gained just 13.4 percent in 2009 and just 5.2 percent in 2010. They had worked hard to stem their losses in 2008, dropping just 23.3 percent. But their speculation cost them in the years that followed. Even if we deduct hedge fund fees, they would still have underperformed U.S. and global stocks from 2007-2011.

Professional Speculators Get Caught With Their Pants Down

| U.S. Stocks | Global Stocks | Hedge Funds | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | +5.49% | +11.16% | +4.2% |

| 2008 | -37% | -41.72% | -23.3% |

| 2009 | +26.46% | +30.4% | +13.4% |

| 2010 | +15.06% | +8.62% | +5.2% |

| 2011 | +2.11% | -7.99% | -8.80% |

* Source:Hedgefundresearch and Morningstar.com

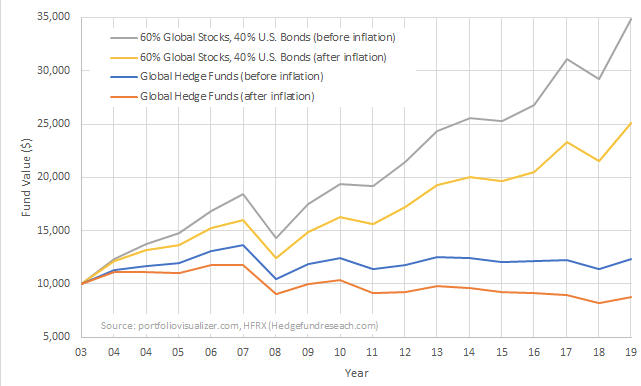

Some might say this comparison isn’t fair. After all, hedge funds can invest in any asset of their choosing. According to sales lore, this helps to protect investors when stocks fall. But when we compare their results to a globally diversified portfolio of ETFs (60% global stocks, 40% bonds) the portfolio of ETFs make them look silly. It beat the hedge funds every single year between 2003 and 2019…including 2008.

In fact, over those 17 years, hedge funds (after fees) didn’t keep pace with inflation.

Diversified Portfolios of ETFs Spank Hedge Funds

| Global Hedge Funds | 60% Global Stocks, 40% U.S. Bonds | Inflation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | +13.40% | +23.10% | +1.88% |

| 2004 | +2.70% | +11.70% | +3.26% |

| 2005 | +2.70% | +7.42% | +3.42% |

| 2006 | +9.30% | +14.35% | +2.54% |

| 2007 | +4.20% | +9.07% | +4.08% |

| 2008 | -23.30% | -22.32% | +0.09% |

| 2009 | +13.40% | +22.00% | +2.72% |

| 2010 | +5.20% | +11.03% | +1.50% |

| 2011 | -8.80% | -1.06% | +2.96% |

| 2012 | +3.51% | +11.94% | +1.74% |

| 2013 | +6.72% | +13.61% | +1.50% |

| 2014 | -0.58% | +4.76% | +0.76% |

| 2015 | -3.64% | -1.10% | +0.73% |

| 2016 | +0.86% | +6.15% | +2.07% |

| 2017 | +0.73% | +15.92% | +2.11% |

| 2018 | -6.70% | -5.96% | +1.91% |

| 2019 | +8.62% | +19.07% | +2.29% |

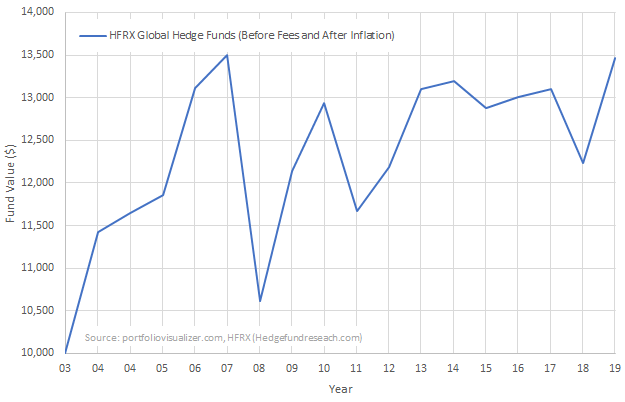

Some people might blame their high fees. Most hedge funds charge fees of 2 percent every year, plus an additional 20 percent of any profits earned. But even if they didn’t charge a penny, they would have beaten inflation by just 1.7 percent annually from 2003-2019. Over the same time period, a globally diversified portfolio of ETFs (60% global stocks, 40% bonds) beat inflation by 5.7 percent per year after fees.

In other words, hedge fund managers could have worked for free, and a globally diversified portfolio of ETFs would have spanked them silly over 17 years.

If Hedge Funds Didn’t Charge Investors Any Fees, They Would Have Beaten

Inflation By Just 1.7% Per Year

2003-2019

All that speculating. All that expertise. All that knowledge. It didn’t help. It hindered. You might think you can predict where stocks are headed. You might think you should hold back because you believe you know when stocks will hit a low. You might think you should suspend your regular dollar-cost averaging until the Coronavirus crisis ends. You might think you’re better than a full-time, professional hedge fund manager. But chances are, you aren’t.

Based on probabilities, such speculation will cost you in the end. After the markets many dips, many surges and many feints, you’ll feel as if a casino bouncer punched you in the gut.

That’s why it’s best to stay the course. Maintain a diversified portfolio of low-cost ETFs. Invest money when you have it…as soon as you have it. Have the courage not to sell.

Most importantly, don’t let fear, greed or ego hurt your long-term gains. After all, short-term thinking will likely cost you plenty.

Andrew Hallam is a Digital Nomad. He’s the author of the bestseller, Millionaire Teacher and Millionaire Expat: How To Build Wealth Living Overseas

Swissquote Bank Europe S.A. accepts no responsibility for the content of this report and makes no warranty as to its accuracy of completeness. This report is not intended to be financial advice, or a recommendation for any investment or investment strategy. The information is prepared for general information only, and as such, the specific needs, investment objectives or financial situation of any particular user have not been taken into consideration. Opinions expressed are those of the author, not Swissquote Bank Europe and Swissquote Bank Europe accepts no liability for any loss caused by the use of this information. This report contains information produced by a third party that has been remunerated by Swissquote Bank Europe.

Please note the value of investments can go down as well as up, and you may not get back all the money that you invest. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.